There are many ways to address a youth mental health crisis, including throwing a massive birthday party for a dog named Gravy.

A sweet-natured chocolate Lab, Gravy quickly became a celebrity to students at Grand Ledge High School after she started working there as a therapy dog in September. She showed off tricks in the hallways with her handler, Dean of Students Maria Capra. When students knelt to pet Gravy, she crawled onto their laps.

So when students learned that Gravy’s first birthday fell just before Thanksgiving break, they asked Capra whether they could throw a party.

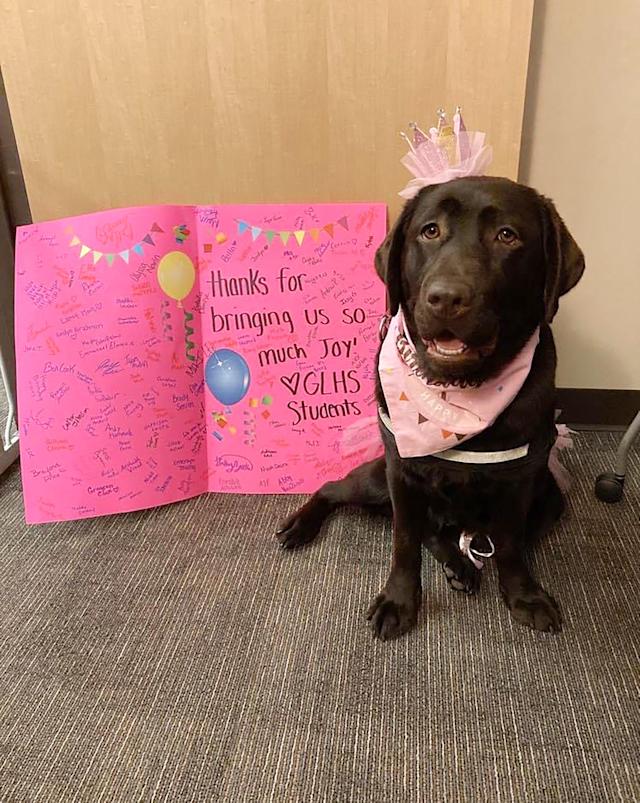

She said sure, thinking it wouldn’t amount to much. Then the student council put up posters around the school, inviting all of the school’s 1,600 students to attend. Students made a crown and a skirt for Gravy, while others set up a donation drive for the local animal shelter in her honor.

On the big day, “I really didn’t know what to expect,” Capra recalled. “I thought it might be a classroom of 30 kids.

“There were several hundred students in this gymnasium.”

The pandemic has been hard on students in Grand Ledge and across the U.S. Many young people experienced isolation, disruption and the loss of loved ones, leading to an alarming rise in suicide rates and prompting the American Academy of Pediatrics to declare a national emergency in children’s mental health.

Schools have responded by hiring social workers, expanding their social-emotional learning curricula and, in some cases, purchasing dogs.

Gravy is one of at least a dozen dogs who have been introduced to students during the pandemic in schools across Michigan.

Districts are buying dogs and covering the costs of their training with their share of Michigan’s $6 billion in federal COVID-19 funds for education.

One reason: The dogs make kids happy.

“He’s kind of like a rock star; when the kids see him coming, they smile,” said Traci Souva, an art teacher at North Huron Schools who handles Chipper, the district’s new golden mountain doodle. “A lot of times the kids will tell Chipper what’s wrong rather than adults, and that’s pretty magical.”

Another reason: The dogs appeal to administrators wary of using one-time federal funds to incur recurring costs like hiring new people.

“We wanted to ensure that we were using the funds in a way that was going to make a lasting impact,” said Bill Barnes, assistant superintendent for Academic Services at Grand Ledge Public Schools.

And one more: Research suggests that the presence of a trained dog lowers children’s stress, fosters a positive attitude toward learning, and smooths interactions between students and other children.

The potential downsides of having dogs in schools — especially sanitation, allergies and student fears — are manageable, Barnes said. The new Grand Ledge dogs are highly trained and hypoallergenic, and they are always with a handler who ensures that no student is forced to interact with the dogs.

A dog trained to work in a school typically costs between $10,000 and $15,000. Districts plan to spend at least $182,000 of their COVID-19 funds to either purchase or rent dogs for emotional support, according to spending plans reviewed as part of a collaborative project involving Chalkbeat, the Detroit Free Press and Bridge Michigan.

That’s a tiny sliver of the federal COVID-19 money available. Districts are spending most of their funds on ventilation improvements to school buildings, hiring additional social workers and counselors, expanding summer school, and providing teacher bonuses.

The court system has long used therapy dogs to ease the nerves of children giving difficult testimony, said Nikki Brown, a dog trainer, school counselor, and the executive director of Canines for Change, a nonprofit that trains dogs for work in schools.