For decades, radiation has been a cornerstone of thyroid cancer care. But it may soon be phased out entirely for many thyroid tumors as emerging research casts doubt on whether it benefits patients.

A study published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that surgery alone might be sufficient to cure the lowest-risk thyroid cancers, and that follow-up treatment with radioactive iodine offers no additional benefit for these patients.

“It’s almost a given that once patients have their thyroid taken out, they get radioactive iodine,” said David Cooper, an endocrinologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Recently, people have been wondering whether it really does what it’s supposed to, whether its potential harms are worth the potential benefits.”

Part of the trouble with answering that question is that low doses of radioactive iodine, which are typically given for low-risk thyroid cancer, aren’t all that bad. Classically, radioactive iodine might cause nausea, discomfort, or in some cases, damage to the salivary glands, but many patients won’t even experience that, Cooper said.

The main burden is that the procedure costs time and money, and brings the remote risk that the radiation itself could cause another cancer.

“Some patients may have a large copay. It’s very time-intensive, that might affect the patient’s income. But the [medical] risks are pretty low,” Cooper said. “That’s why it sort of drifted along without anyone carefully analyzing it.”

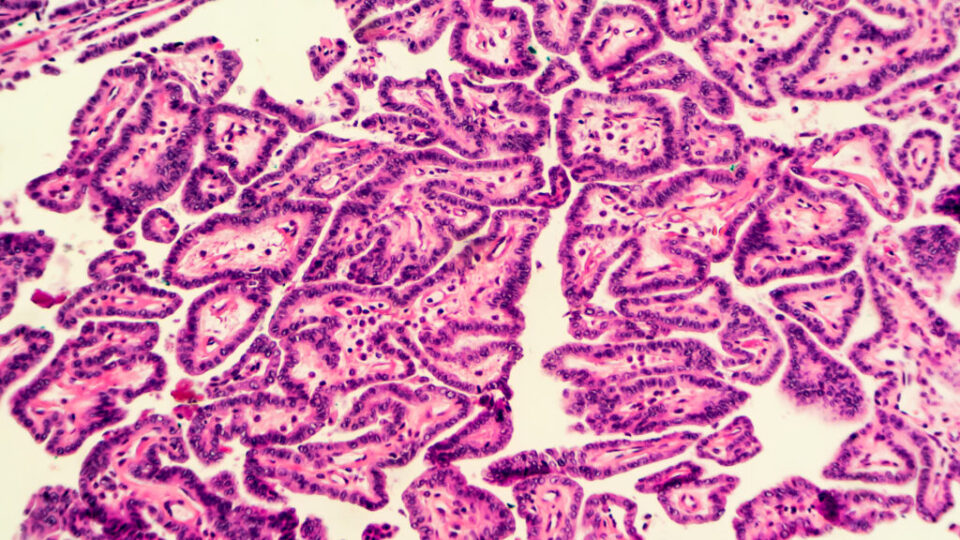

Radioactive iodine works a bit like a Trojan horse against cancer. The thyroid needs iodine to produce its specific set of hormones, so thyroid cells and thyroid cancer cells pump in the radioactive iodine-131 just as readily as any other isotope of the element. Once inside, the radioactivity kills the cell. The idea is to clean up any thyroid cancer cells that might have been left behind after surgery, specifically for cancers known as differentiated thyroid cancers, which include follicular and papillary thyroid cancer. Radioactive iodine is not used for other forms, such as medullary or anaplastic thyroid cancer.

“In the ’90s, there was a retrospective study showing that radioactive iodine could reduce mortality and relapse in thyroid cancer patients,” said Sophie Leboulleux, an oncologist who worked on the study as a scientist at Gustave-Roussy Cancer Campus in France and is now at Geneva University Hospitals. “But times have changed. Thyroid cancers are not discovered at the same stages they were 25 years ago.”

Thyroid cancer is found more frequently now because CT scans and ultrasounds done on the head and neck for other reasons may incidentally catch thyroid cancer, too. Often, these are small, low-risk tumors, Leboulleux said. In these cases, clinicians have started wondering if surgery alone might be sufficient, sparing patients from the added cost of radiation. In 2012, Leboulleux worked on another study that found roughly 30 millicuries of radiation was just as good as a much larger dose typically given for low-risk thyroid tumors.

“For low-risk [thyroid cancer] we felt there might not be any need for it,” she said. “So we decided to do another study to see if radioiodine therapy was even useful.”

So, Leboulleux and her colleagues recruited 730 patients with low-risk, differentiated thyroid cancer with tumors 2 centimeters or less in width. Half of them were randomly sorted to receive no radioactive iodine after thyroid surgery, and the other half received about 30 millicuries of radiation. After three years, there was no difference in the two groups when it came to new treatments, relapses, or abnormal biological markers. The team will continue to follow the study participants for several more years, but Leboulleux doesn’t expect any changes.

The study is the first hard evidence that post-operative radioactive iodine is very likely useless for these low-risk thyroid cancers, said Johns Hopkins’ Cooper, who also wrote an editorial on the study. “The current recommendation is not to give radioactive iodine in low-risk patients like these, but it’s based on weak evidence and expert opinions,” Cooper said.

“This paper won’t change the recommendation, but doctors and scientists accept randomized trials. So, I think it will change hearts and minds on this topic,” he said. That should help doctors and patients feel more comfortable foregoing radiation after thyroid surgery, Leboulleux said. Ultimately, she thinks that will be good for patients.

“Radiation is just one more worry for a patient. Once you know that you don’t need it, I don’t think you should receive it,” Leboulleux said.

Radioactive iodine still helps for high-risk thyroid cancer, where the malignancy has already spread throughout the body. Whether follow-up radiation is beneficial for more intermediate-risk thyroid cancers is still an open question, Leboulleux added. That is something she hopes to investigate next.